Highland Journey

Highland Journey

In the spirit of Edwin Muir

2006

Published Birlinn 2009

Introduction

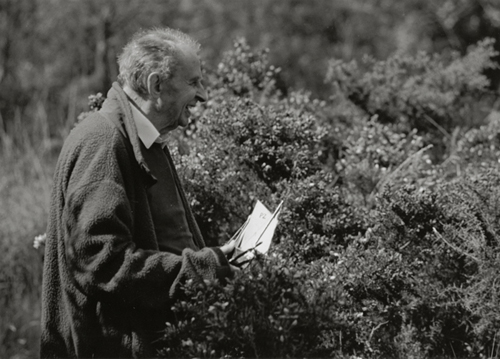

In June of 1934 the writer and poet Edwin Muir borrowed a car from his friend, fellow Orcadian and contemporary, Stanley Cursiter, then the Director of the National Galleries of Scotland, and set out on a tour around Scotland. In the introduction to his book Scottish Journey, published the following year, he states,

‘… my intention in beginning it was to give my impression of contemporary Scotland; not the romantic Scotland of the past nor the Scotland of the tourist, but the Scotland which presents itself to one who is not looking for anything in particular, and is willing to believe what his eyes and ears tell him.’

Several writers have made journeys throughout Scotland: Boswell and Johnson in the 18th century, Robert Louis Stevenson in the 19th, and Muir, James Campbell and Michael Russell in the 20th. The last two both tip a hat to Muir. It could be argued that historically, Muir is the most interesting: he writes before the cataclysmic social, economic and political change brought about by World War Two and yet much of it has strong resonances for today. He worries at the nature of Scottish identity, and what he saw as its erosion by (in those days, English) incomers, and he comments on tourism and depopulation.

During the early months of 2006 I began to plan an extended journey around the Scottish Highlands and Orkney inspired by Muir’s travels – not as a writer, but as a photographer. It’s difficult to estimate, but Muir’s journey in the whole of Scotland probably lasted two to three weeks, while spending six days travelling through the Highlands on his way to Orkney. I knew that my journey would take a great deal longer. It seems paradoxical, but photography is a slower process than writing. The writer records their thoughts and impressions, sometimes long after the experience as Muir did, whereas the photographer has to photograph what is there. You can’t photograph a thought. Subjects have to be contacted and arrangements made; research in situ has to be carried out and due attention has to be paid to The Light. There’s a great deal of enforced inactivity involved in photography.

The section of Muir’s ‘Journey’ that covered the Highlands amounts to approximately a quarter of the book and is full of fascinating and eloquent anecdote and description. There is, however, very little reference to the political, social and economic issues facing the Highlands and Orkney at that time, save for some subjective opinion. As a romantic socialist and quasi-nationalist, it’s clear that he had knowledge of these issues, but he doesn’t directly deal with them. Again and again, Muir refers to ‘impressions’; he is not attempting an academic socio-political study but rather a personal response: “a thin layer of objectivity super-imposed on a large mass of memory”. I wished to divert, not just from Muir’s route, but from his remit, by commenting on some of the major contemporary issues facing these remote areas.

As an Orcadian, Muir considered himself to be both an insider and an outsider from Scotland; as a Lowlander, I have a similar relationship with the Highlands, which even today is radically different, socially and economically, to my home town of Edinburgh. Naturally, I had made many previous visits to the Highlands, so I cannot say that I was without preconceptions, however I have tried to be true to Muir’s principle in that I would respond to what I saw. This then, was to be a highly partial account of one person’s impressions of the Highlands.

I was aware that I was attempting a project that was very traditional – and unfashionable – in concept. I wanted to work with a 5x4in camera and black and white film; to produce highly formal and constructed pictures. I intended following the example, not just of Muir, but of classic documentary photographers like Paul Strand, who spent three months in South Uist in 1954. The resulting pictures, published as “Tir A’ Mhurain” are not only fine examples of photographic art, but an important historical record of a community experiencing protracted and radical change. It did occur to me that I was (ambitiously and arrogantly) attempting to do for the whole of the Highlands and Orkney what Strand did for tiny South Uist, in the same time frame.

I purchased a thirty year old large format folding camera and various lenses on an internet auction site and finally located a second hand campervan small enough to easily navigate Highland roads, but which could accommodate a darkroom. The shower compartment was converted for this purpose and a scanner installed, so that I could process sheets of film, scan them and view them ‘on the road’ on a laptop computer. Further embracing the digital age I took with me a compact digital camera to use as a ‘visual notebook’.

In the event I spent a total of 80 days in the van between the beginning of June and the end of October 2006, and made some 75 final pictures from about 250 exposures, from which I have selected 50. I covered some 5,000 miles, but not as a contiguous journey as I had hoped and imagined, since various personal demands meant that I had to break my journey on occasions.

The original text in my book was gleaned and embellished from a journal kept throughout the ‘Journey’.

You can read a review of the book here.

In the spirit of Edwin Muir

2006

Published Birlinn 2009

Introduction

In June of 1934 the writer and poet Edwin Muir borrowed a car from his friend, fellow Orcadian and contemporary, Stanley Cursiter, then the Director of the National Galleries of Scotland, and set out on a tour around Scotland. In the introduction to his book Scottish Journey, published the following year, he states,

‘… my intention in beginning it was to give my impression of contemporary Scotland; not the romantic Scotland of the past nor the Scotland of the tourist, but the Scotland which presents itself to one who is not looking for anything in particular, and is willing to believe what his eyes and ears tell him.’

Several writers have made journeys throughout Scotland: Boswell and Johnson in the 18th century, Robert Louis Stevenson in the 19th, and Muir, James Campbell and Michael Russell in the 20th. The last two both tip a hat to Muir. It could be argued that historically, Muir is the most interesting: he writes before the cataclysmic social, economic and political change brought about by World War Two and yet much of it has strong resonances for today. He worries at the nature of Scottish identity, and what he saw as its erosion by (in those days, English) incomers, and he comments on tourism and depopulation.

During the early months of 2006 I began to plan an extended journey around the Scottish Highlands and Orkney inspired by Muir’s travels – not as a writer, but as a photographer. It’s difficult to estimate, but Muir’s journey in the whole of Scotland probably lasted two to three weeks, while spending six days travelling through the Highlands on his way to Orkney. I knew that my journey would take a great deal longer. It seems paradoxical, but photography is a slower process than writing. The writer records their thoughts and impressions, sometimes long after the experience as Muir did, whereas the photographer has to photograph what is there. You can’t photograph a thought. Subjects have to be contacted and arrangements made; research in situ has to be carried out and due attention has to be paid to The Light. There’s a great deal of enforced inactivity involved in photography.

The section of Muir’s ‘Journey’ that covered the Highlands amounts to approximately a quarter of the book and is full of fascinating and eloquent anecdote and description. There is, however, very little reference to the political, social and economic issues facing the Highlands and Orkney at that time, save for some subjective opinion. As a romantic socialist and quasi-nationalist, it’s clear that he had knowledge of these issues, but he doesn’t directly deal with them. Again and again, Muir refers to ‘impressions’; he is not attempting an academic socio-political study but rather a personal response: “a thin layer of objectivity super-imposed on a large mass of memory”. I wished to divert, not just from Muir’s route, but from his remit, by commenting on some of the major contemporary issues facing these remote areas.

As an Orcadian, Muir considered himself to be both an insider and an outsider from Scotland; as a Lowlander, I have a similar relationship with the Highlands, which even today is radically different, socially and economically, to my home town of Edinburgh. Naturally, I had made many previous visits to the Highlands, so I cannot say that I was without preconceptions, however I have tried to be true to Muir’s principle in that I would respond to what I saw. This then, was to be a highly partial account of one person’s impressions of the Highlands.

I was aware that I was attempting a project that was very traditional – and unfashionable – in concept. I wanted to work with a 5x4in camera and black and white film; to produce highly formal and constructed pictures. I intended following the example, not just of Muir, but of classic documentary photographers like Paul Strand, who spent three months in South Uist in 1954. The resulting pictures, published as “Tir A’ Mhurain” are not only fine examples of photographic art, but an important historical record of a community experiencing protracted and radical change. It did occur to me that I was (ambitiously and arrogantly) attempting to do for the whole of the Highlands and Orkney what Strand did for tiny South Uist, in the same time frame.

I purchased a thirty year old large format folding camera and various lenses on an internet auction site and finally located a second hand campervan small enough to easily navigate Highland roads, but which could accommodate a darkroom. The shower compartment was converted for this purpose and a scanner installed, so that I could process sheets of film, scan them and view them ‘on the road’ on a laptop computer. Further embracing the digital age I took with me a compact digital camera to use as a ‘visual notebook’.

In the event I spent a total of 80 days in the van between the beginning of June and the end of October 2006, and made some 75 final pictures from about 250 exposures, from which I have selected 50. I covered some 5,000 miles, but not as a contiguous journey as I had hoped and imagined, since various personal demands meant that I had to break my journey on occasions.

The original text in my book was gleaned and embellished from a journal kept throughout the ‘Journey’.

You can read a review of the book here.